--by @Josh_Suchon

--by @Josh_Suchon

Marcus Allen was the subject of NFL Networks’ most recent “A Football Life” this week, which brought the bizarre feud between Allen and Al Davis back to the limelight. I’ve always been fascinated, amazed, appalled, and incredibly curious how Allen got so deep in Davis’ doghouse.

“I never quite understood what made things go bad,” Allen says, in the documentary.

Whatever the story, Al Davis took it to his grave.

After watching the film, pouring through old archives, and consulting the raw data, here’s my impression of what happened: Davis hated that Allen was a training camp holdout four of five years, Davis signed other players because he thought Allen had become injury-prone and not as productive, and Davis thought Allen was hiding from competition.

However, there must be more to the story than that. If that was the full story, why would Davis not just say it? Even for the notoriously private Davis, who rarely talked to the press, what’s the harm in that explanation?

Filmmaker Ice Cube conducted what’s believed to be the final interview before Davis’ death. Their exchange over Marcus Allen went like this:

Ice Cube: “Did you think he was a true Raider?”

Al Davis: “At one time, he was. Yeah, he was.”

Ice Cube: “What happened with him?”

Al Davis: “I’m not going to tell you. It’s a deeper story than you even dream, that I was well aware of. I just have a certain approach to life.”

Even the fearless Ice Cube didn’t press Davis further. Who knows the real answer? Only a handful of people. Former head coach Tom Flores is one of them.

When asked about the sour relationship, Flores said, “The only issue that happened with Marcus, when I was there, is (Allen) held out one year. Al didn’t like people who held out. He did not like that. Having said that, I also remember once, when I was already gone. We were talking about the team and (Davis) said, ‘this is a good team. You would like this team. But we need to get Marcus in here.’ That’s what he said.”

Flores paused, then continued. “I know what the rift was over. It had nothing to do with his football playing. That’s as far as I’m going to go.” Flores laughed nervously, and the hosts didn’t press him further.

Even from his grave, Davis wields remarkable power to keep his most loyal employees silent.

The NFL Network’s documentary on Allen didn’t get us any closer to learning the “deeper story” on the rift between Allen and Davis. It didn’t provide many details on Allen’s true relationship with Bo Jackson.

But it was still good a good film. It did shed additional light on the holdouts and why Allen waited so long to vent publicly. Allen explained why he returned to the Coliseum – at the invitation of Davis’ son, Mark, the current owner – to light the torch for Al Davis.

If you have a bunch of time on your hands and want a year-by-year recap of Allen’s career with the Raiders, the brewing conflict between Davis and Allen, the raw numbers on what it was really like when Allen and Jackson were teammates, then get yourself comfortable and keep reading.

1982

Allen was drafted 10th overall by the Raiders, who were still in Oakland at the time, but would move to Los Angeles months later.

Allen was drafted 10th overall by the Raiders, who were still in Oakland at the time, but would move to Los Angeles months later.Even though Allen was the Heisman Trophy winner, there were doubts about his NFL future. Allen was prone to fumbles at USC, the Raiders’ offense was geared around running the fullback, and Paul Maguire even wondered on ESPN’s Draft Day program if Allen would get moved to wide receiver.

Despite that, the Raiders changed their offense to become more tailback-oriented to suit Allen. They even moved Kenny King, the tailback from the Super Bowl winning team two years earlier, to fullback.

In nine games (the strike eliminated weeks 3-9), Allen averaged 4.4 yards per carry and 77.4 yards a game. Allen was the Rookie of the Year, the Raiders went 8-1, and even though they were upset by the Jets in the playoffs, they had a budding star on their hands.

Later in life, Allen wondered if Davis didn't like him because it wasn't Davis' decision to draft him. I find it hard believe that Al Davis would ever draft somebody he didn't want. That's just not Al's style.

1983

The Raiders went 12-4 in the regular season and steamrolled all three opponents in the playoffs en route to a Super Bowl title.

In the regular season, Allen was very good, but still not the focus of the offense. He averaged 17.7 carries a game (he wasn’t in the Top 10 in the league). Only four times did he carry more than 20 times in a game. Allen averaged 3.8 yards per carry and 63.4 yards a game. The fumbles were a big concern, as his 14 led the league (12 were lost).

Allen’s strength was in his versatility. He caught 68 passes (the most of his career) for 590 yards, and he was 4-of-7 passing with three touchdowns.

1984

Allen was arguably the biggest star in the NFL, but it still wasn’t evident in his carries. Allen still only averaged 17 carries a game, and never had more than 22 rushes in any game. Allen averaged 4.2 yards a carry and 73 yards a game. He still touched the ball a lot, adding 64 more catches and a league-leading 18 total touchdowns (13 rushing, 5 receiving).

The defending Super Bowl champs went 11-5, but still finished third in the highly competitive AFC West, behind 13-3 Denver and 12-4 Seattle. In the wild card playoff game, Seattle beat the Raiders at the Kingdome.

Allen was 10th in the league in rushing attempts. He wanted to carry the ball more, and made it known to Davis.

1985

Unleashed in his fourth season, Allen compiled one of the greatest rushing seasons in NFL history. Allen led the league with 1,759 yards rushing (an average of 109.9 yards a game), and caught another 67 passes for 555 yards.

Allen went over 100 yards rushing in the final nine games, and 11 of the last 12. The Raiders won 10 of those last 12 games. Allen averaged 23.8 carries a game (the most of his career and second-most in the NFL), and gained an average of 4.6 yards per rush.

1986

After his MVP season, Allen’s production dropped considerably. The Raiders offensive line wasn’t very good and Allen took a pounding. Allen missed the 4th, 5th and 8thgames of the season with injuries, and didn’t start in three other games. Napoleon McCallum (a fourth-round pick that year) started in his place.

Allen’s yards-per-carry dropped to a career-low 3.6 yards, his total rushing yards dropped exactly 1,000 to 759 total, and he averaged 16 carries a game.

The Raiders lost their final three games, finished 8-8 that year, and didn’t make the playoffs for the first time in four years. One fumble didn't cost a game, or a season. But it was the turning point in a season and it would be a long time before the Raiders mystique returned.

1987

The Raiders’ needs were acutely evident in their draft that year. The drafted tackle John Clay in the first round, and tackle Bruce Wilkerson in the second round. Concerned that Allen might be wearing down physically, they drafted Penn State running back Steve Smith in the third round, and took quarterback Steve Beureline in the fourth round.

Then in the seventh round, they drafted Bo Jackson.

It was a classic Al Davis move. He loved speed, power, and doing anything that made him look smarter than the rest of the NFL. Jackson was the No.1 overall pick by the Tampa Bay Bucs a year earlier, but chose baseball because the Bucs cost him his final season of college baseball by flying him on a chartered plane for an interview. Nobody thought he’d really change his mind, but the Raiders mystique convinced Jackson to play football once baseball season was over.

Jackson’s debut came Nov. 1, exactly four weeks after Kansas City Royals’ final regular season game. Everything about that regular season was bizarre.

Allen rushed for 136 yards, then 79 yards, as the Raiders started the year 2-0. Then came a players strike, which wiped out the games in Week 3.

In Week 6, the final game of “strike-ball,” the “Raiders” suited 13 players from their 45-man roster, plus four more who began the year on injured reserve. Allen still didn’t cross the line. The "Raiders" lost to a “Chargers” team that started zero scabs, and non-union Rick Neuheisel took a break from USC Law School to play quarterback.

In the first game with all the union players back, Allen was held to 29 yards on 11 carries, and the real Raiders were thrashed by Seattle. The team was fractured by those who crossed the line and the union hard-liners. Their record was 3-3, and this was the environment as Jackson made his debut. Then-coach Tom Flores initially wasn’t sure how to use both of his Heisman Trophy winners.

This is a breakdown of how the carries went the next four games:

- Nov. 1 at New England: Allen 16 carries, 41 yards, 1 TD, 5 catches for 60 yards; Jackson 8 carries, 37 yards, 1 catch for 6 yards. The Patriots won 26-23.

- Nov. 8 at Minnesota: Allen 11 carries 50 yards, 4 catches for 12 yards; Jackson 12 rushes for 74 yards, 1 catch for 7 yards. The Vikings won 31-20.

- Nov. 15 at San Diego: Allen 13 carries for 82 yards, 3 catches for 21 yards; Jackson 8 rushes for 45 yards, 3 catches for 26 yards. The Chargers won 16-14.

- Nov. 22 vs. Denver: Allen 11 carries for 44 yards, 4 catches for 60 yards; Jackson 13 carries for 98 yards and 2 TDs, 5 catches for 20 yards. The Broncos won 23-17.

At some point during that stretch, Flores said Allen volunteered to move to fullback -- “I had them both in the same backfield and it was a lot of fun.”

Then came the legendary Monday Night Football game in Seattle when Jackson showed this two-sport thing was the real deal. On his 27th birthday, Jackson ran 18 times for 221 yards and two touchdowns, including the famous 91-yard TD run, another when he ran over Brian Bozworth, and also had a 14-yard TD reception in a 37-14 rout that ended the Raiders losing streak at seven games.

This wasn’t one of those brutal Seahawks teams from the 1970s either. Going into the game, Seattle was 7-3, had beaten the Raiders five straight times (averaging seven sacks and five turnovers in those games), and had won the previous two meetings 33-3 and 37-0.

Forgotten is that Allen also had 18 carries, going for 76 more yards in the game. Still, the game made it clear that Jackson was the new star for the Raiders. The damage from the strike had fractured the club, but Jackson gave them somebody to rally around. Allen was officially in the background, but still the ultimate team player.

Jackson credited his big night to the “great blocking I had. Marcus (Allen) threw some great blocks." And quarterback Marc Wilson added, “both of 'em can block well, and Marcus has been so unselfish that's really helped us. Most of the time it's Marcus throwing the lead block.”

After his coming-out party on national TV, Jackson rushed 19 times for 78 yards, caught four passes for 59 yards and a touchdown, and the Raiders beat the Bills 34-21. They were back to 6-7 and dreaming of a Jackson-fueled run to the playoffs.

Those hopes dashed the next week. Jackson sprained his ankle three rushes into the game, the Raiders rushing attack went silent, the lowly Chiefs beat them and eliminated them from the playoffs.

Jackson missed the final two games of the season with the ankle injury. Allen was held to 35 yards on 14 carries by the Browns, then a respectable 75 yards on 18 carries against the Bears. The Raiders finished the season with a record 5-10 overall, 1-2 non-union.

Allen’s final totals: 16.6 carries a game, 3.8 yards a rush, 62.8 yards rushing a game.

Jackson’s final totals: 11.6 carries a game, 6.8 yards a rush, 79.1 yards rushing a game.

1988

This was the first year the Raiders went into training camp knowing Bo Jackson would be their featured running back, but they’d need Marcus Allen to hold down the fort until after baseball season ended.

Allen’s production to start the year: 28 carries for 88 yards in a win, 22 carries for 70 yards in a loss, 14 carries for 53 yards in a loss, 22 carries for 56 yards in a win, 11 carries for 53 yards and a broken bone in his left arm in a loss. Allen didn’t play the sixth game.

Jackson’s debut came on Oct. 16, two weeks after his baseball season ended, and the night after Kirk Gibson hit the most dramatic home run in baseball history. It was the Raiders’ seventh game, and their record was 2-4. Allen was practicing with his left arm in a cast, trying to make one-handed catches out of the backfield.

It’s not hard to see why Jackson was welcomed with open arms and viewed as a potential savior to the season. As promised, head coach Mike Shanahan didn’t start Jackson. Instead, he entered on the second play, swept right for 8 yards, swept left for 3 yards and a first down, went left for 6 more, caught a pass for 5 yards, sat out a play to catch his breath, then gained 5 more yards.

When it was over, Jackson had 20 carries for 71 yards and a score, Allen had 11 carries for 20 yards, and the Raiders had a much-needed win.

When it was over, Jackson had 20 carries for 71 yards and a score, Allen had 11 carries for 20 yards, and the Raiders had a much-needed win.

The next week, Jackson gained 25 and 20 yards on his first two carries against the Saints. He pulled a hamstring on the second run, the same injury that prevented him from being a 30-30 man in baseball that year, and didn’t play the rest of the game.

Jackson played the rest of the season with a tender hamstring, and Allen had a cast on his arm. Neither did anything very noteworthy. Jackson never went over 100 yards. His game-high was 85 yards, in a 9-3 upset win at San Francisco. That gave the Raiders three straight wins, a 6-5 record to pull into a first place tie in a weak division, and renewed hope.

Then they lost four of five to end the year 7-9, and missed the playoffs for a third straight year. In the MNF encore in Seattle, Jackson was held to 31 yards on 13 carries.

The side-by-side comparisons of the Heisman Trophy winning backs for the year:

Allen: 15 games, 14.9 carries a game, 3.7 yards a carry, 55.4 yards a game.

Jackson: 10 games, 13.6 carries a game, 4.3 yards a carry, 58.0 yards a game.

1989

For two seasons now, Marcus Allen carried the load for the first third of the season, then shared the backfield with Bo Jackson, dutifully became the lead blocker, remained a pass-catching threat, played hurt frequently, and despite what was assuredly a bruised ego, didn’t complain.

His relationship with Al Davis wasn’t great, but it wasn’t bad. Then came the holdout of 1989 that changed everything.

Allen was due to make $1.1 million. Jackson would get paid $1.356 million for playing just over a half season, although $996,000 was deferred. The only running back getting paid more than Allen was Eric Dickerson at $1.2 million. Allen wanted a multi-year guaranteed contract, just like Jackson had. Some key passages from this LA Times article on the holdout. [Teammates] voted him their most valuable player in four of the last five seasons. As unsure of himself as he often seems off the field, he is a towering figure among the Raiders with a long history of sucking it up for the team.

There are Raider officials who think his 1,759-yard league-leading season in 1985 was a marvel that has never been fully appreciated, since Allen did so much of it on his own, operating behind something less than an overpowering line.

Playing behind worse lines, he has been injured for most of the last three seasons, raising questions about what he has left. He remains valuable because of his ability to play hurt, his all-around game and his grace in accommodating Bo Jackson by becoming a 205-pound fullback.

He is said to want a three-year guaranteed extension, at Jackson's numbers.

Halfbacks are not normally tendered guarantees, since they're such natural targets, but at least part of Jackson's contract is guaranteed.

Allen didn't attend the team's spring mini-camp. He did go to the facility in El Segundo to lift weights, but was told that if he wasn't going to practice, he'd have to leave. Let's just assume Allen didn't like that much.

(Allen’s agent Ed) Hookstratten has called Davis, a source says, but Davis hasn't returned any of the calls. Hookstratten and Davis were once friendly, but several sources say that Davis is angry at him, too.

Allen’s holdout ended nine days before the regular season opener. He didn’t play in any of the exhibition games. Davis never budged and never talked to the press during the five-week holdout. Allen’s contract remained the same, but nothing else would ever remain the same between Davis and Allen.

"The reasons for the holdout are personal,” Allen told reporters, when he returned to camp. “I don't want to elaborate on them. I just felt it was time to go back to work." A friend of Allen’s said, “(Marcus) just wanted to be shown some respect.”

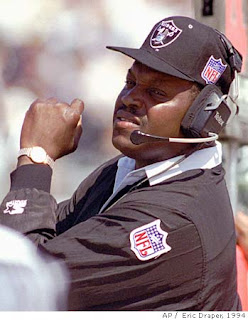

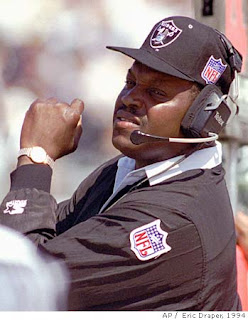

In the four September games with Jackson playing baseball, the rushing duties were shared by Allen (52 carries), Steve Smith (31 carries) and Vance Mueller (17 carries). The Raiders went 1-3, Mike Shanahan was fired, and Art Shell took over as head coach.

In the four September games with Jackson playing baseball, the rushing duties were shared by Allen (52 carries), Steve Smith (31 carries) and Vance Mueller (17 carries). The Raiders went 1-3, Mike Shanahan was fired, and Art Shell took over as head coach.

“I have no intention of playing fullback,” Allen said. “I’ll discuss it with the coaches if they have other ideas.” Beyond the physical told of playing fullback, Allen added, “Put it this way: I’m not ready to be a role player yet. My problem is, I’ve been such a nice guy. I’ve been trying to make everybody happy and I’ve been making myself miserable.”

The Raiders won Shell’s debut over the lowly Jets on Monday Night Football. The running back controversy didn’t materialize because Allen left in the third quarter with a torn ligament in his right knee.

Allen didn’t play the next eight games. The Raiders went 5-3 with Jackson as their feature back.

Jackson had a few monster games (19 carries for 144 yards and a 73-yard TD run against the Redskins, followed by 13 carries for 159 yards and a 92-yard TD run against a Bengals team that would reach the Super Bowl). A string of leg injuries also kept Jackson quiet for three straight weeks (11 carries for 54 yards against Houston, 20 carries for 64 yards against New England, 14 carries for 44 yards against Denver).

Jackson had a few monster games (19 carries for 144 yards and a 73-yard TD run against the Redskins, followed by 13 carries for 159 yards and a 92-yard TD run against a Bengals team that would reach the Super Bowl). A string of leg injuries also kept Jackson quiet for three straight weeks (11 carries for 54 yards against Houston, 20 carries for 64 yards against New England, 14 carries for 44 yards against Denver).

Allen returned in Week 14. It remained mostly the Jackson show (22 carries, 114 yards, a 50-yard burst). But late in the game, Allen’s number was called twice. On 4th-and-2, Allen got three yards and kicked in the groin. Allen came out to catch his breath, Mueller was stuff at the 1-yard line, then Allen returned and scored the game-winning touchdown on a classic over-the-top leap with 40 seconds remaining.

The Raiders’ record was 8-6. They led in the wild-card race. But losses to Seattle and the Giants in the final two weeks meant no playoffs for a fourth straight year, and questions on where the Raiders would call home in 1990.

Jackson was held to 35 yards on 10 carries in the season finale. He finished the year with 950 yards in nine games, an average of 5.5 yards per carry. Allen’s 69 carries were a career low, but he would reach lower lows in the next few years.

1990

With no real options elsewhere, Al Davis kept the team in Los Angeles. It was assumed that Marcus Allen would be gone, especially after the Raiders signed running back Greg Bell from the Rams. But the Raiders held onto Allen, reportedly after Art Shell lobbied for him to stay, and Allen was a holdout for a second straight year.

Allen was actually one of nine holdouts on the opening day of training camp, although the running back was back in camp soon thereafter.

The annual waiting game for Jackson lasted six games, and produced the following results: Allen had 73 carries and averaged 4.04 yards a carry; Steve Smith had 36 carries and averaged 4.03 yards a carry; and Bell had 47 carries and averaged 3.30 yards a carry.

The Raiders were 5-1, their best start in years, and Jackson was returning. The speculation was that Allen would get shipped out with the trading deadline approaching. But in that sixth game, Bell sprained his right ankle, and the Raiders would leave themselves vulnerable to depth concerns if Allen was traded.

For the next 10 games, the Allen-Jackson tandem worked better than at any other time. Allen always started at tailback, Jackson usually got the most carries, and Smith played fullback. The Raiders won their final five games to finish 12-4 and clinch the AFC West.

Jackson averaged 12.5 carries a game, 5.6 yards a carry, went over 100 yards in three straight games, missed a fourth 100-yard game by one yard, and scored five touchdowns.

Allen’s carries per game went from 12.1 before Jackson to 10.6 after Jackson. He averaged 3.8 yards a rush, scored 12 touchdowns, led all running backs with 15 receptions, and only fumbled once all year.

Allen’s carries per game went from 12.1 before Jackson to 10.6 after Jackson. He averaged 3.8 yards a rush, scored 12 touchdowns, led all running backs with 15 receptions, and only fumbled once all year.

The running back controversy ended in the playoffs, early in the third quarter, even though nobody knew it at the time. Jackson was torching the Bengals. His ran for 34 yards on an electrifying run, and he had 77 in the game on just six carries.

But that would be his last run. Jackson was tackled from behind and suffered a hip injury that didn’t look very serious at the time. In fact, Jackson insisted after the game he would play the next week against the Bills. In reality, he never played football again.

With Jackson sidelined, the 30-year-old Allen turned back the clock to 1985, gaining 140 yards on 21 carries as the Raiders beat the Bengals and were one victory from the Super Bowl. The next week, the Bills routed the Raiders 51-3 in the AFC Championship Game.

1991

Marcus Allen didn’t hold out in 1991. Instead, he filed an anti-trust lawsuit against the NFL. Allen’s four-year contract had expired after the 1988 season, but he was forced to play for a third straight year under the terms of his old contract, unable to seek free agency, and the Raiders were unwilling to trade him.

Bo Jackson’s football career was over. Allen showed in the playoffs that he was still a dominating running back. But that didn’t stop Al Davis from signing former All-Pro running backs to compete with Allen.

First was Roger Craig, fresh off a costly fumble late in the NFC Championship Game against the Giants that cost the 49ers a third straight trip to the Super Bowl. Craig entered the season as the backup. Allen wasn’t looking over his shoulder for Jackson’s early-October arrival. But in a 30-point opening game loss at Houston, Allen tore the posterior cruciate ligament in his left knee while making a cut on the artificial turf.

First was Roger Craig, fresh off a costly fumble late in the NFC Championship Game against the Giants that cost the 49ers a third straight trip to the Super Bowl. Craig entered the season as the backup. Allen wasn’t looking over his shoulder for Jackson’s early-October arrival. But in a 30-point opening game loss at Houston, Allen tore the posterior cruciate ligament in his left knee while making a cut on the artificial turf.

"It's a damn shame that you can run out on the turf, and nobody touches you, and you hurt yourself," Allen said. "It's a . . . shame. That stuff should not be used by anybody. No human being should have to walk on that stuff.”

Allen missed the next eight games with the injury. When he returned for the 10th game, the Raiders record was 5-4. Allen, Craig and Nick Bell split the rushing duties over the next four games -- Allen averaged 6.1 carries a game -- as the Raiders reeled off four straight wins to move into first place in the AFC West with a 9-4 record.

Allen's teammates say Davis and Allen do not speak to each other, let alone hold real conversations. Everyone here feels the strain. No one here comments about it for attribution.

Davis was asked what he thinks of Marcus Allen as a player?

"I'm paying him $1.1 million," Davis snapped. "That's what I think of him."

Allen was asked about Davis as an owner and a friend. He laughed. It was a nervous laugh.

"No comment," Allen said. He laughed again.

What about when he finally reported in 1989 and was listed as the team's No. 4 running back? Another nervous laugh. He was silent and stared intently at nothing before speaking.

"When you understand everything and look at the big picture," said Allen, "you understand the reason why you have been relegated to such a status and you realize that in time it will change. I'm thinking about writing a book. I've got a lot to say, but not now. I will say it has been a difficult situation and that no one knows what I've been through. I've just tried to be smart and intelligent about these things. And I guess the one constant on why I have survived here is the fact that I can still play."

The promising season ended poorly. The Raiders lost the final three regular season games, squeaked into the playoffs, and lost to the Chiefs in the wild card game.

Allen averaged a team-high 4.6 yards per carry. Craig, definitely past his prime, led the team in carries with 162 (more than double anybody else), yet had the lowest yards per carry at 3.6 among the four primary running backs.

1992

The next former All-Pro running back signed to compete with Marcus Allen and provide insurance because of Allen’s recent injury history (the Raiders story), or to ensure Allen would remain on the sidelines (Allen’s story) was Eric Dickerson.

Allen responded by holding out, again, this time for about a month. It was the fourth time in five years Allen either reported late, or missed significant time in training camp. Allen was "stuck" with the same $1.1 million contract for the fourth straight season. By now, Allen knew that holding out wasn’t going to get him a new contract; it was just a protest.

Allen responded by holding out, again, this time for about a month. It was the fourth time in five years Allen either reported late, or missed significant time in training camp. Allen was "stuck" with the same $1.1 million contract for the fourth straight season. By now, Allen knew that holding out wasn’t going to get him a new contract; it was just a protest.

When he finally reported, Allen didn’t talk to the media. One Raiders official pointed to Allen’s recent injuries, and said, “figure out his salary per carry.”

Dickerson, who’d led the league in rushing four times in his career, was a fraction of his former self. But he was productive enough, and stayed healthy, to keep Allen on the sidelines for most of the season. Dickerson averaged 3.9 yards a carry (the lowest of his career), and went over 80 yards just twice in his 15 games.

Allen never started a game, carried the ball just one time in four different games, and had six carries or less in 14 of the 16 games. Allen did manage to catch 28 passes, tied for third-most on the team.

The Raiders lost four straight to begin the year, and were 6-7 when Allen finally unloaded on Davis. He chose to record an interview that aired at halftime of the Raiders’ Monday Night Football game against Miami.

"What do you think of a guy who has attempted to ruin your career?" Allen told Al Michaels. "When someone messes with your livelihood--this is what I've wanted to do since I was 8 years old, and this very thing has been taken away from me and not, I don't think, for a business reason, but for a personal reason."

Asked if it was a personal vendetta, Allen said: "No question about it."

In conversations with Davis, Allen said: "He told me he was going to get me and he has. I don't know for what reason, but he told me he was going to get me.

"I think he has tried to ruin the latter part of my career, tried to devalue me and tried to stop me from going to the Hall of Fame. It has been an outright joke to sit on the sidelines and not get an opportunity to play.”

Clearly, Davis was annoyed at Allen’s holdouts, and didn’t want to pay Allen any extra money, especially in light of his recent injuries and drop in production. What baffles so many Raiders fans, to this day, is why Davis didn’t just release or trade Allen – if he hated him that much.

This is where Davis’ pride and ego, and most of all, vindictive personality took over.

"I'm taking it personal," Shell said. "I'm disappointed in (Allen). To say that I told him I was out of it and had no control over it is wrong. I dispute that.

"Look, Al Davis has a lot of input in our personnel decisions and rightfully so, because he understands personnel. He doesn't always agree with me when I make a decision on who is going to play and who is not going to play. But, in the final analysis, I was hired to make the decisions and, if those decisions don't work out, then I'll be fired, because I am the head coach. I, one person, made the choice as to who would be the featured running back."

"Look, Al Davis has a lot of input in our personnel decisions and rightfully so, because he understands personnel. He doesn't always agree with me when I make a decision on who is going to play and who is not going to play. But, in the final analysis, I was hired to make the decisions and, if those decisions don't work out, then I'll be fired, because I am the head coach. I, one person, made the choice as to who would be the featured running back."

That choice was Eric Dickerson, who was acquired in an off-season trade. Allen, who held out during training camp, eventually became the third back, behind Dickerson and Nick Bell. The leading rusher in Raider history, Allen is used on short-yardage, goal-line and third-down plays.

"The reason I made the choice was that Eric was here the whole training camp," Shell said. "So was Nick Bell. Marcus wasn't. . . . You can't have a rotation of three backs. So I tried to figure out a way for each of them to make a contribution to our football team."

[snip]

Shell concedes that he has talked to Allen about leaving the Raiders.

"He's come in and asked about being traded," Shell said. "I said to him, 'Marcus, I'm not going to give you away. I'm not into that for selfish reasons. I don't want to trade you because I think you're a hell of a football player, and I don't want to just give you away to somebody out there and hurt our football team.' "

The damage was done though. Allen’s interview provided the proof of the long-standing belief that Davis was calling all the shots. Allen knew he would finally become a free agent after the season, and he could vent five years of pent-up frustrations.

1993

Indeed, Allen never played for the Raiders after the 1992 season. He signed with the Chiefs, and enjoyed a career re-birth at age 33.

Allen played five more seasons with the Chiefs, missing just three games. He never went over 900 yards rushing in a season and averaged exactly 4.0 yards a carry. He kept his nose for the end zone, however, scoring 44 touchdowns in those five years and finished his career with 123. That was the most in the NFL when he retired, and remains third-most to this day.

It’s more myth than legend that Allen tortured the Raiders when they’d play head-to-head twice each season. Yes, Allen had games of 132 yards and 124 yards rushing against the Raiders. He also had games of 24 yards (in the first matchup), and the final four games against the Raiders saw him rush for 34, 64, 13 and 26 yards. The Chiefs were 9-1 in those games, but that’s mostly because they were simply the better team.

Even without his five years in Kansas City, Allen probably would have enjoyed his rightful place in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. But those years sealed his induction.

Most of Raider Nation took Allen’s side in the feud. Allen was incredibly respected by his teammates. For the Raider Haters around the country, the hate started with Al Davis, so they took Allen’s side as well.

In my final analysis, these are the truths that I believe:

- Davis deeply resented the holdouts.

- Allen’s performance was slipping and he was missing more games. Davis was justified in bringing in new running backs each year because tailback is a volatile position prone to injuries.

- Jackson clearly outplayed Allen when they were teammates. Allen was initially a good soldier when Jackson arrived, but Allen’s pride was hurt more than he’d care to admit.

- Davis should have released or traded Allen, at least one year before Allen departed via free agency, and perhaps two years earlier. Because Davis didn’t do that, Allen’s claim that Davis was intentionally trying to sabotage his career carries more weight. Yes, depth is always needed at running back, but there’s a certain dignity granted to the league’s elite players. For example, the 49ers traded Joe Montana to make room for Steve Young, rather than stashing Montana on the bench as an insurance policy in case Young got hurt. Davis should have done that, and he could have hand-picked an NFC team where Allen wouldn’t directly impact the Raiders.

- I doubt we'll never learn the "deeper story" that Davis cryptically told Ice Cube ... unless Tom Flores leave the answer in his will. Gosh that would be awesome if he did.

###

That’s something EPSN analyst Jesse Palmer said during the Pinstripe Bowl between Syracuse and West Virginia. My first thought was that’s a bunch of nonsense. I thought it was one of those statements that analysts make because it sounds good. Or it’s something that coaches say to motivate their players, and the analyst just regurgitates it.

That’s something EPSN analyst Jesse Palmer said during the Pinstripe Bowl between Syracuse and West Virginia. My first thought was that’s a bunch of nonsense. I thought it was one of those statements that analysts make because it sounds good. Or it’s something that coaches say to motivate their players, and the analyst just regurgitates it. In order to get a true indication of whether winning a bowl game gives you “momentum” for the next season, you’d need to sample at least the last five years, if not the last 10 years. I’m curious about momentum, but not curious enough to do all that research. If somebody wants to do it, I’d love to see the numbers.

In order to get a true indication of whether winning a bowl game gives you “momentum” for the next season, you’d need to sample at least the last five years, if not the last 10 years. I’m curious about momentum, but not curious enough to do all that research. If somebody wants to do it, I’d love to see the numbers.